Morrison's inept pandemic response has cost lives and livelihoods

By Ranting Panda, 28 June 2021

Australia has been very fortunate in the limited impact that COVID-19 has had on it compared to many other countries. Since the first Australian case was reported in 2020, there have been 910 deaths to date (Department of Health, 2021c). While this is 910 deaths too many, it is relatively few deaths compared to many other countries, including Italy, India, Indonesia, and the United States.

Much of Australia's success in limiting the impact of COVID, has not been from its federal government, but because of the swift and decisive action taken by its state governments. In fact, the federal government was directly responsible for the spread of the virus in Australia, as well as for most of the deaths. There are five key areas that the incompetence and inaction of Australia's federal government worsened the situation:

- Ruby Princess cruise ship

- Aged Care

- Quarantine

- Contact tracing

- Vaccine roll-out.

Ruby Princess cruise ship

On 8 March 2020, the Ruby Princess cruise ship departed Circular Quay, Sydney, for an 11-day cruise to New Zealand and return. The passengers were not notified that there had been 158 cases of people from the previous voyage with coronavirus-like symptoms (Mao 2020).

The ship returned to Sydney on 19 March 2020. The federal government controls international borders and had deemed the voyage to be a 'low-risk' because its route had only taken it to New Zealand (Mao 2020). Following the federal government's guidelines for international passengers deemed low-risk, New South Wales Health officials allowed the passengers to disembark without testing. Even though these were returning international travellers, neither the federal government or the New South Wales government bothered to quarantine the passengers or keep track of where the passengers went.

One day later, three of the passengers were diagnosed with COVID-19. Within five days, more than 133 of the passengers were found with COVID, many of whom had travelled interstate and mingled with the general community.

The federal government could have prevented the ship from docking. Prior to the Ruby Princess, the Morrison government had banned international cruise ships from docking in Australia. However, it exempted four ships from this ban; the Ruby Princess was one of them (Mao 2020).

The Commonwealth Department of Health required the passengers to self-isolate for 14 days after arrival in Sydney, and had published a fact-sheet explaining how to do this. However, Australian Border Force incorrectly advised passengers that the 14 days commenced from the date they departed Sydney, which was 11 days earlier than it should have started. This meant that passengers thought they only had to self-isolate for three days after arrival in Sydney (Special Commission of Inquiry into the Ruby Princess, 2020, item 2.16).

In all, more than 700 passengers from the Ruby Princess tested positive for COVID, infecting thousands across Australia because of the federal government allowing it to dock, failing to quarantine passengers, and allowing passengers to travel unmonitored throughout the country. This monumental failure by the Morrison government could be considered ground-zero for the unchecked spread of COVID-19 throughout the nation.

Aged Care

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety published its final report in March 2021. It noted that 'Access to aged care is controlled by the Commonwealth Government' (Vol 2, p 191). 'Funding for aged care is insufficient, insecure and subject to the fiscal priorities and wide-ranging responsibilities of the Australian Government. This affects access to, and the quality and safety of, care' (Vol 2, p 188). Since 2015-16, Australian government expenditure on aged care for people aged over 70, has decreased as a percentage of GDP per capita (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, 2021, Vol 2, p 191). The Royal Commission found that since the mid-1980s, the decline in spending by the Commonwealth Government is even more noticeable for people aged over 80 (Vol 2, p 191).

Morrison's failure to address shortfalls in Commonwealth-funded aged care facilities resulted in 685 deaths across Australia. Of these, 655 were in Victoria, 28 in New South Wales, one in Queensland, and one in Tasmania (Department of Health, 2021b). While some commentators tried to blame state premiers for the deaths in their state, specifically Premier Dan Andrews in Victoria, these facilities were the responsibility of the Commonwealth government, with the state governments having no control over them.

On 1 October 2020, the Royal Commission published an interim report that made several recommendations regarding addressing COVID-19 in aged care facilities. The Commonwealth government implemented all recommendations. Recommendation 4 of this report recommended that the 'Australian Government should establish a national aged care plan for COVID-19 through the National Cabinet in consultation with the aged care sector' (Vol 5, p 172). It is almost inconceivable that the Australian government failed to do this when the pandemic commenced more than six months earlier, particularly considering it was already known that the elderly were most susceptible. As dozens and dozens of people died in aged care, the federal government still failed to establish a plan for addressing COVID-19 in aged care facilities until a Royal Commission recommended it.

The Australian government's failure to act on aged care cost the lives of 685 elderly people.

Quarantine

Section 51 of the Australian Constitution gives the federal government its legislative powers. This is where the Commonwealth government gets its power to control international migration. This same section also gives the Commonwealth government responsibility for quarantine. It makes sense that if the Commonwealth government is bringing people into the country, then the Commonwealth government should be responsible for quarantining them. But not the Morrison government. While the federal government was happy to continue bringing people into the country from overseas, it abdicated its responsibility for quarantine. Mind you, it was more than happy to detain asylum seekers and refugees in remote detention facilities for years at a time, even though they had not committed any crimes. But I digress. Instead, the Commonwealth government placed the burden of quarantine on the state governments, who were not prepared for this. Morrison washed his hands of quarantine, even as the states requested he help to create dedicated quarantine facilities. The state governments had to act immediately to help process the numbers of international travellers that the federal government was bringing into the country. The state governments did this by quickly repurposing hotels into quarantine centres.

Hotels are not suitable for quarantine for several reasons, not least of which is they have central air-conditioning which facilitates the spread of airborne viruses. In Victoria, this was brought to prominence when its hotel quarantine program failed spectacularly, resulting in the loss of hundreds of lives and a State of Disaster being declared, plunging Victoria into a prolonged lockdown.

On 13 March 2020, the Commonwealth government established a National Cabinet to ensure a consistent approach to addressing COVID-19 throughout Australia. The National Cabinet acknowledged that much of the spread of COVID was due to international arrivals. On 27 March 2020, the National Cabinet implemented a 14-day mandatory quarantine period for international arrivals, without establishing quarantine facilities. It left this to the state governments, who then scrambled to establish hotel quarantine programs. Based on this, Victoria's Hotel Quarantine Program was established over one weekend in March 2020. The program was implemented within 36 hours of it being conceived, which placed considerable strain on Victoria's health resources, exacerbated by there being no warning of its implementation and no blueprint for its operation (Victorian Government, 2020, p 18).

A decision was made to use private security to guard the hotels, although it wasn't clear who made the decision. It was not one made by any Victorian minister. Victoria Police admitted that their preference was for private security to provide the first tier of security arrangements, with Police to be used as a back-up (Victoria Government, 2020, pp 20-21). Whoever made the decision, didn't follow appropriate procurement guidelines and awarded the contract to a company who had not been awarded the State Purchase Contract for security. Additionally, that company then sub-contracted to other security service providers. There was no risk assessment in awarding the contract and the scope of the contract was ill-defined. An Inquiry into Victoria's tragic Hotel Quarantine Program, found that the security guards were not the appropriate mechanism for protecting the hotels and monitoring persons in quarantine, because private security firms tend to have a highly-casualised workforce. The Inquiry found that engaging an organisation with a more structured, fully salaried workforce would have been more effective, such as Victoria Police (Victorian Government, 2020, p 24).

The Inquiry further observed, 'Both the State and Commonwealth governments were aware, prior to 2020, of the possibility of a pandemic and its potentially devastating consequences. However, none of the existing Commonwealth or State pandemic plans, contained plans for mandatory, mass quarantine. Indeed, the concept of hotel quarantine was considered problematic and, thus, no plans for mandatory quarantine existed in the Commonwealth's overarching plans for dealing with pandemic influenza. Prior pandemic planning was directed at minimising transmission (for example, via voluntary isolation or quarantine at home) and not an elimination strategy' (Victorian Government, 2020, p 15).

The Quarantine Hotel Programme in each state was necessary because of the volume of international arrivals the federal government allowed into Australia, and who then spread throughout the country.

It's not like the Commonwealth government didn't have time to prepare for a pandemic. There was, after all, one in 2003, when the bird flu (H5N1) spread throughout much of Asia, and again in 2009, with swine flu (H1N1). In 2011, a review was conducted of the federal government's response to the swine flu pandemic. The 2011 Review of Australia’s Health Sector Response to the (H1N1) Pandemic 2009 included recommendations for national quarantine facilities. Specifically, one of the recommendations stated, 'The roles and responsibilities of all governments for the management of people in quarantine, both at home and in other accommodation, during a pandemic should be clarified. A set of nationally consistent principles could form the basis for jurisdictions to develop operating guidelines, including plans for accommodating potentially infected people in future pandemics and better systems to support people in quarantine' (Victorian Government, 2021, pp 87, 91). Ten years on and this recommendation has not been acted on by the federal government.

The Victorian government did bungle the hotel quarantine in mid-2020 through engaging private security firms and not managing the containment of those quarantined. However, hotel quarantine was never going to be suitable. This had been identified ten years earlier in the 2011 H1N1 review in which a national response was recommended. Yet, the Commonwealth Pandemic Plan still fails to address mandatory or mass quarantine as happened during COVID (Victorian Government, 2020, pp 88-89).

Several states have been crying out for dedicated quarantine centres to be established. Even after the hotel quarantine debacle last year that cost lives, Prime Minister Morrison has been arguing over the proposal by the Victorian government for a dedicated quarantine facility to be established near Avalon Airport. Morrison is adamant that the dedicated facility supplements hotel quarantine, rather than replaces it (Crowe, 2021). Morrison has also played politics with a similar suggestion by the Queensland government who had proposed a 1000-bed camp at Wellcamp Airport near Toowoomba. More than 12-months after the hotel quarantine programs were established by state governments at the behest of the federal government, Morrison is still arguing about dedicated facilities, criticising solutions proposed by state governments (Chen, 2021).

Contact tracing

On 26 April 2020, the federal government's COVIDSafe application was released. This was a mobile phone app that would allegedly help identify people exposed to COVID-19. Prime Minister Morrison proudly touted the application as Australia's way out of lockdowns.

A Senate Select Committee has been convened to look into all aspects of the government's pandemic response. Their final report is due for release by 30 June 2022. The Interim Report released in December 2020 has been scathing. The Committee found that the COVIDSafe app relied on using Bluetooth technology in a way that it was never designed to be used, namely to connect untrusted devices to each other (Parliament of Australia, 2020).

The app cost more than $5 million and was promoted by a $64 million marketing campaign. Yet six months after its release, it had detected a whopping 17 potential exposures to the virus. This despite there being around 30,000 cases in that time (Department of Health, 2021a).

Vaccine roll-out

The federal government is responsible for Australia's vaccination program. However, it has bungled this with an incredibly slow roll-out, as well as issuing contradictory messages around the efficacy of AstraZenica and who is eligible for it. The federal government played politics with the vaccination program by by-passing the state governments and dealing directly with private medical clinics and GPs (Murphy, 2021). This so that the federal government could deal with 'friendly' clinics, rather than 'nit-picking' state governments. Of course, state governments are far better suited to rolling out a mass vaccination program, then the friendly GP down the road.

The procurement of the vaccines was slow and put Australia at a disadvantage. Larger markets, such as the United Kingdom and the United States were ordering vast quantities of vaccines as early as May 2020 (Murphy, 2021). It wasn't until four months later, in September 2020, that the Australian government ordered 85 million doses of vaccines, comprised of AstraZeneca and a vaccine developed by the University of Queensland (Harvey, Koloff & Wiggins, 2021). In December 2020, the UQ vaccine was scrapped after trials were giving false positives for HIV. Although Pfizer approached the government in June 2020, it wasn't until November 2020 that the government ordered 10 million doses. The federal government has since ordered another 40 million doses of Novavax, which will not be delivered until late 2021. It has also ordered 25 million doses of Moderna, which will commence delivery in late 2021 and be finalised in 2022.

Both AstraZeneca and Pfizer began arriving in Australia in February 2021. Following criticism of the slow roll-out, the government claimed that the European Union blocked 3.1 million doses of AstraZeneca to Australia, in order to meet EU demand. The EU however, claims it was only 250,000 doses that were redirected from Australia to EU nations (Hawke 2021). Either way, it is well less than 10% of Australia's orders that were impacted by the EU's decision to prioritise European nations over other nations. Additionally, AstraZeneca can also be manufactured in Australia. This excuse by Prime Minister Morrison is lame.

Australia's sluggish vaccine roll-out is affecting people and businesses as lockdowns loom whenever clusters of COVID appear. The vaccine roll-out is at least two months behind schedule (Ting, Scott & Palmer, 2021).

The contradictory messages from the government included warnings about the dangers of AstraZeneca and changing the age limits that could access it, as well as implying that there was no rush to be vaccinated (Tingle, 2021). AstraZeneca was approved by Australia's pharmaceutical regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, for use in people aged over 18. Initially, AstraZeneca was available for all adults, then the government recommended it only for over-50s, then to over-60s. As a result, many people are refusing to take AstraZeneca, even though the likelihood of serious adverse reactions is exceptionally low. The likelihood of death from AstraZeneca is one in two million; the chance of being struck by lightning is four times this, while the chance of dying from Aspirin is 200 times greater than dying from AstraZeneca (Grills, 2021). This isn't some theoretical figure postulated by academics based on guestimates; it is based on reviewing the affects of more than two billion COVID-19 vaccinations administered globally.

Australia has far more AstraZeneca than Pfizer at this stage, and the refusal by many to take it because of media fear-mongering and contradictory government advice, has exacerbated the low take-up of vaccinations. Following a National Cabinet meeting on 28 June 2021, Morrison announced that AstraZeneca would be available for any adult of any age who asks for it (Clun, 2021). This may help to improve the roll-out of vaccinations, however, the government will need to address the fear-mongering and its own mixed messages around this vaccine.

Despite the horrendous death toll in aged care facilities, only one third of aged care workers have so far been vaccinated (Lucas, 2021). The National Cabinet meeting of 28 June 2021, has decreed that vaccinations will be mandatory for aged care workers (Clun, 2021).

The Morrison government is under fire from every state and territory leader for its botched vaccination roll-out (Remeikis, 2021). New South Wales premier, Gladys Berejiklian, criticised the Commonwealth government's lack of pandemic planning as the greater Sydney area was forced into a lockdown in late June 2021. This, just days after Prime Minister Morrison praised Berejiklian for her 'gold standard' pandemic response in not locking the state down despite a growing number of infections. Berejiklian initially resisted lockdown so that she could demonstrate that the Victorian government's lockdowns were an over-reaction. This political ploy backfired spectacularly when the Delta-strain of the virus spread uncontrolled through Sydney infecting dozens of people, forcing Berejiklian to institute a lockdown (Raper, 2021). This essentially justified Victoria's rapid lockdown response in containing the spread of the virus. Now, instead of returning Morrison's praise, Berejiklian has joined other state and territory leaders in criticising Morrison's incompetent pandemic response, calling for him to ramp up the vaccine roll-out to reduce the likelihood of future lockdowns and lessen the impacts on health and the economy. Berejiklian went on to state, 'Our GPs want to do more. They want more doses and they also want more GPs to come online. That is necessary. That is not something that the New South Wales government can control' (Remeikis, 2021). This isn't something that any state can control; the supply of vaccines is purely in the hands of the federal government.

Conclusion

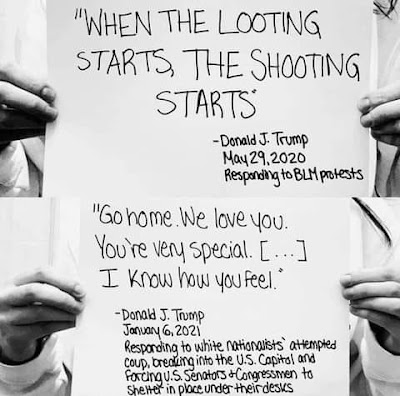

The Morrison government's response to COVID-19 is almost as inept as former president Trump's COVID-19 response. Trump's ineptitude cost more than 420,000 lives in the US before he was spectacularly booted from office.

If it wasn't for the strict lockdowns and decisive actions taken by the various state governments, Australia would have faced far more deaths than it has. Senator Katy Gallagher, Chair of the Senate Select Committee on COVID-19, stated 'It was the states who took the big brave decisions at the right time and forced the hand of the Federal Government, that was resisting pressure to take stronger action. Without the strong advocacy displayed by state premiers for bolder measures — particularly by NSW and Victoria — Australia's experience with the pandemic could have been very different. Thank goodness for the states' (Roy, 2020).

Morrison continues criticising the states every time there is a lockdown, however, those lockdowns are the result of the international travellers that he continues to allow into the country, the lack of dedicated quarantine facilities for those travellers, and his bungled vaccine program. Each of these things are directly attributable to Morrison and the federal government. It is only the federal government who can fix each of these issues. Morrison has had more than 12 months to create purpose-built quarantine facilities to REPLACE hotel quarantine, which will be necessary for international travel to continue. And of course, improving the vaccine roll-out will help protect the community and enable it to return to relative normality. Instead of a competent and strong leader who can address these factors, we have a Prime Minister who shirks responsibility and blames others.

References

Chen, D, 2021, Scott Morrison proposes Brisbane COVID-19 quarantine hub, rejects Wellcamp Airport proposal, ABC News, 25 June 2021, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-24/pm-covid-19-quarantine-hub-hotel-army-barracks-brisbane-wellcamp/100242960.

Clun, R, 2021, AstraZeneca vaccine available to all adults, jabs mandated for aged care workers, Brisbane Times, 28 June, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/politics/federal/mandatory-vaccines-for-aged-care-workers-quarantine-to-be-separated-20210628-p5850h.html.

Crowe, D, 2021, Deal in sight for $200m quarantine facility near Avalon Airport, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 June, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/deal-in-sight-for-200m-quarantine-facility-near-avalon-airport-20210603-p57xwb.html.

Department of Health, 2021a, Coronavirus (COVID-19) current situation and case numbers, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers.

Department of Health, 2021b, COVID-19 cases in aged care services – residential care, 26 June, viewed 26 June 2021, https://www.health.gov.au/resources/covid-19-cases-in-aged-care-services-residential-care.

Department of Health, 2021c, COVID-19 deaths by age group and sex, viewed 26 June 2021, https://www.health.gov.au/resources/covid-19-deaths-by-age-group-and-sex.

Grills, N, 2021, Getting a Covid jab is safer than taking Aspirin, Pursuit, 21 June, viewed 23 June 2021, University of Melbourne, https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/getting-a-covid-jab-is-safer-than-taking-aspirin.

Harvey, A, Koloff, S, & Wiggins, N, 2021, How Australia's COVID vaccine rollout has fallen short and left us 'in a precarious position', ABC News, 24 May, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-24/australia-covid-vaccine-rollout-what-went-wrong/100151396.

Hawke, J, 2021, European Union denies claim it blocked shipment of 3.1 million AstraZeneca COVID vaccines to Australia, ABC News, 7 April, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-04-07/eu-denies-blocked-shipment-over-3-million-vaccines-to-australia/100052134.

Lucas, C, 2021, Two-thirds of staff in aged care homes not vaccinated, The Age, 26 June, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.theage.com.au/politics/victoria/two-thirds-of-staff-in-aged-care-homes-not-vaccinated-20210624-p583vv.html.

Mao, F, 2020, Coronavirus: How did Australia's Ruby Princess cruise debacle happen?, BBC, 24 March, viewed 26 June 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-51999845.

Murphy, K, 2021, Scott Morrison was so keen to own a successful vaccine rollout he forgot about the risk of overseeing a debacle, The Guardian, 17 April, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/apr/17/scott-morrison-was-so-keen-to-own-a-successful-vaccine-rollout-he-forgot-about-the-risk-of-overseeing-a-debacle.

Raper, A, 2021, Gladys Berejiklian insists COVID-19 lockdown is based on health advice, not politics, ABC News, 27 June, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-27/analysis-gladys-berejiklian-delayed-nsw-covid19-lockdown/100247422.

Remeikis, A, 2021, Gladys Berejiklian voices vaccine frustration at federal government ahead of national cabinet meeting, The Guardian, 28 June, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/jun/28/gladys-berejiklian-voices-frustration-at-federal-government-ahead-of-national-cabinet-meeting.

Roy, T, 2020, COVID-19 inquiry makes six recommendations including a permanent rise in JobSeeker, ABC News, 9 December, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-09/covid-committee-interim-report-released-six-recommendations/12968080.

Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, 2020, Aged Care and COVID-19: a special report, 30 September, viewed 26 June 2021, https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/aged-care-and-covid-19-special-report.

Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, 2021, Final report, 1 March, viewed 26 June 2021, https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/final-report.

Parliament of Australia, 2020, Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 - Interim report, December 2020, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/COVID-19/COVID19/Interim_Report/section.

Special Commission of Inquiry into the Ruby Princess, Report, 14 August, viewed 26 June 2021, https://www.rubyprincessinquiry.nsw.gov.au/report.

Ting, I, Scott, N, & Palmer, A, 2021, Untangling Australia’s vaccine rollout timetable, ABC News, 30 May, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-28/untangling-australia-s-covid-vaccine-rollout-timetable/100156720.

Tingle, L, 2021, If the public has vaccine hesitancy, the government has developed strategy hesitancy, ABC News, 22 May, viewed 28 June 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-22/if-public-has-vaccine-hesitancy-government-strategy-hesitancy/100154798.

Victorian Government, 2021, COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry - Final Report, 21 December, viewed 27 June 2021, https://www.quarantineinquiry.vic.gov.au/.